Achievements

fath |

From 2012 to 2019, research has been mostly focused on the influence of the acidic microenvironment on the tumor cell metabolism, under the supervision of Prof. O. Feron, in the Pole of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at IREC.

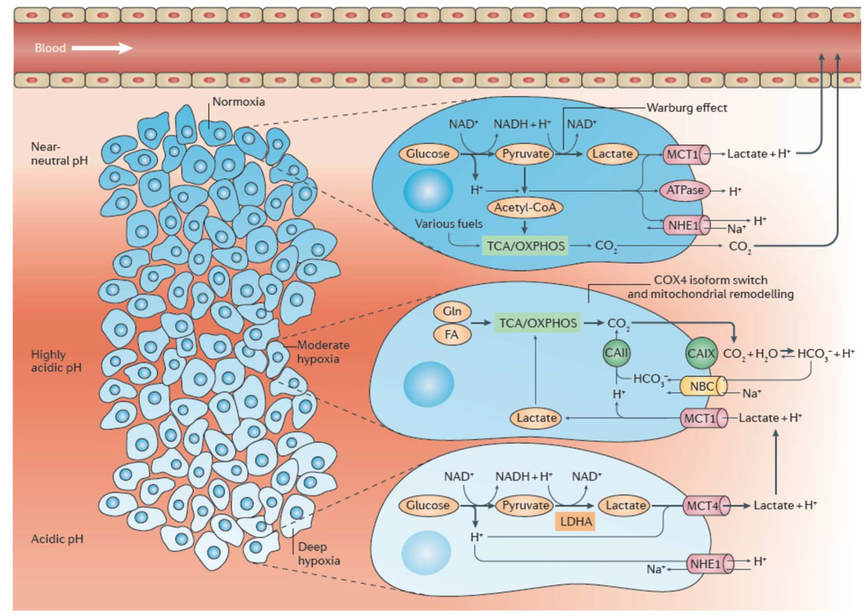

Acidosis, like hypoxia, is nowadays considered as a hallmark of most human cancers. Extracellular pH (pHe) has been determined in a wide variety of cancers to be significantly more acidic than in normal tissues, with values ranging from 5.9 to 7.2. Importantly, although tumor metabolic peculiarities, such as the exacerbated glycolytic metabolism or the respiration-driven CO2 hydration, directly account for the acidification of the tumor microenvironment (Figure 1; Corbet & Feron, 2017a), whether and how chronic acidosis may itself influence metabolism remained elusive when we started this study.

Acidosis drives a metabolic switch from glucose to glutamine utilization

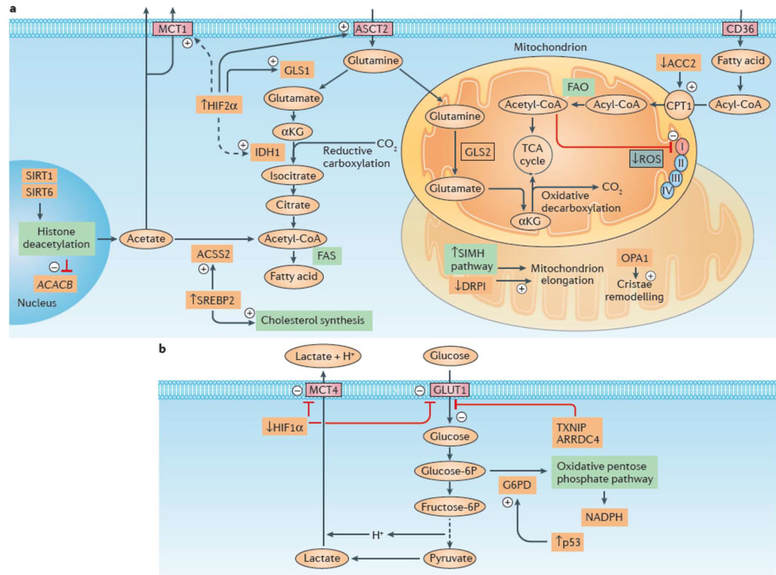

By using a long-term selection of tumor cells able to survive and proliferate under acidic conditions (pH 6.5) and state-of-the-art metabolomic approaches (e.g. Seahorse XF technology, metabolic flux analysis using 13C-labeled substrates), we found that despite a similar proliferation rate in tumor cells adapted to acidic pH and in parental cells (maintained at pH 7.4), a metabolic shift from a largely glucose-dependent metabolism towards the preferential use of glutamine was actually observed in response to chronic acidic conditions (Corbet et al., 2014). In this study, the adaptation of human cancer cells of distinct origins to the extracellular acidification was associated with an increase in SIRT1-driven protein deacetylation leading to a reduction in hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) activity and abundance concomitantly to a net increase in HIF-2α activity and expression. Major targets of the latter were identified including the glutamine transporter SLC1A5, the glutaminase isoform GLS1, and the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH1) supporting the cytosolic reductive metabolism of glutamine and a corresponding shift in the response to therapeutic interventions (Figure 2). Indeed, in vitro and in vivo experiments documented that acidosis accounts for a net increase in tumor sensitivity to inhibitors of SIRT1 and glutaminase GLS1, highlighting the influence that tumor acidosis and metabolism exert on each other (Corbet et al., 2014). Still in a therapeutic aim, we also showed that chitosan-based nanoparticles loaded with siRNA targeting the glutamine transporter led to a dramatic tumor growth inhibition upon peritumoral but also systemic administration in mice (Corbet et al., 2016a).

Acidosis links protein acetylation modifications and fatty acid metabolism dysregulation

We then investigated, even more in depth, the molecular mechanisms sustaining this acidosis-induced metabolic shift. We first wondered whether deacetylation occurring under chronic acidosis was a generic mechanism or if it impacted on specific proteins (such as HIF factors). To address this question, we set up a large-scale proteomic experiment (AcetylScan) aiming to identify the nature of acetylated/deacetylated proteins in acidosis-adapted cancer cells. We showed that more than 700 lysine residues (from more than 500 non-redundant proteins) were differentially acetylated between the two pH conditions (i.e. pH 7.4 and 6.5) (Corbet et al., 2016b). While we confirmed a global deacetylation pattern in the cytosolic and nuclear proteins (including histones), a net increase in the acetylation of mitochondrial proteins was unexpectedly observed and confirmed using isolated mitochondria preparations from three distinct human tumor cell lines. After documenting that this mitochondrial hyperacetylation was occurring non-enzymatically, we examined whether fatty acids could be the source of acetyl-CoA supporting this phenomenon (glucose being not available in acidosis-adapted cells) (Figure 2). Cell treatment with 14C-labeled substrates, followed by mitochondria isolation and immunoprecipitation of acetylated proteins, indicated that under acidic conditions, more fatty acids contributed to acetyl-CoA generation and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation. Using specific siRNA targeting ACSL1 (acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1) or CPT1 (carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1), we actually found a significantly higher sensitivity of acidic pH-adapted tumor cells to this inhibition of the transport (and further β-oxidation) of fatty acids in mitochondria. Similar anticancer effects were observed in vitro and in vivo with etomoxir, a pharmacological inhibitor of CPT1 (Corbet et al., 2016b). Finally, we identified several subunits of the electron transport chain complexes being hyperacetylated in acidosis-adapted cells. Among them, NDUFA9 acetylation restrained complex I activity to prevent reactive oxygen species (ROS) production as a consequence of mitochondrial overfeeding.

Unexpectedly, we found that acidosis-adapted tumor cells, not only used exogenous fatty acids to fuel the TCA cycle with acetyl-CoA, but simultaneously stimulated glutamine metabolism to support citrate production and lipogenesis. We were intrigued by the concomitance of fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and fatty acid synthesis (FAS) in these cells. FAO and FAS are usually described as mutually exclusive in healthy tissues. There is indeed a logic behind the need to spare newly synthesized FA from degradation. The molecular basis for this regulation involves the enzyme acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) that exists as two major isoforms: the cytosolic ACC1 and the mitochondrial ACC2. ACC catalyzes the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA which is a substrate for fatty acid synthase (FASN) but also inhibits CPT1, thereby preventing the simultaneous occurrence of FAS and FAO (Figure2) .

a) Stimulated fatty acid metabolism in response to acidosis is depicted. Note the double fate of glutamine, with mitochondrial oxidative metabolism supporting the canonical tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, while cytosolic reductive carboxylation of glutamine-derived α‑ketoglutarate (αKG) sustains fatty acid synthesis (FAS). The latter pathway is supported by increased expression and activity of hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF2α), which in turn accounts for the upregulation of the glutamine transporter ASC-like Na+-dependent neutral amino acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) and glutaminase 1 (GLS1) and is associated with increased expression of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1). The synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol is also increased upon acidosis-driven activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (SREBP2), which supports the expression of acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member 2 (ACSS2), a cytosolic enzyme that catalyses the activation of acetate into acetyl-CoA for use in lipid synthesis. Concomitant fatty acid oxidation (FAO) and FAS under acidosis is rendered possible through downregulation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 (ACC2) upon sirtuin 1 (SIRT1)- and SIRT6‑mediated histone deacetylation of the gene that encodes ACC2, acetyl-CoA carboxylase β (ACACB). The risk of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) production is also limited by the non-enzymatic acetylation and consecutive partial inhibition of respiratory chain complex I. In addition, acidosis prevents hypoxia-induced mitochondrial fragmentation via a decrease in the interaction between dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1; also known as DNM1L) and mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1) and promotes mitochondrial elongation in a stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfusion (SIMH) pathway-dependent manner. Acidosis also increases the amount of oligomeric complexes of the mitochondrial dynamin-related GTPase (OPA1), thereby increasing cristae morphology and numbers, a remodelling event associated with better respiration efficiency and resistance to cell death.

b) Alterations in glucose metabolism under acidosis. A decrease in HIF1α abundance and activity (resulting from direct acetylation) reduces the expression of glycolytic enzymes as well as the glucose transporter GLUT1 and the lactate transporter MCT4. Upregulation of thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) and its paralogue arrestin domain-containing protein 4 (ARRDC4) under lactic acidosis substantially contributes to inhibition of tumour glycolytic phenotypes via the inhibition of glucose uptake in breast cancer cells. The fraction of glucose taken up by the cancer cell is redirected away from lactate production towards the oxidative branch of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), an alternative metabolic route facilitated by a p53‑dependent increase in glucose‑6‑phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD)71. CPT1, carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1; fructose‑6P, fructose‑6‑phosphate; glucose‑6P, glucose‑6‑phosphate. ‘+’ denotes an activating stimulus; ‘–’ denotes an inhibitory pathway (from Corbet & Feron Nat Rev Cancer 2018).

Our observations point the pathways fueling the synthesis and/or oxidation of lipids as key determinants of tumor cell adaptation to acidic conditions and thereby provide a new rationale for the use of drugs interfering with fatty acid metabolism to treat cancer. This is actually making echo to recent studies showing that targeting fatty acid metabolism is a very promising therapeutic strategy to treat cancer and developing metastases (Corbet and Feron, 2017b). Moreover, our studies indicate that acidosis-adapted cancer cells rely on mitochondrial respiration; this OXPHOS-dependent metabolism has been reported in various tumor types for many life-threatening cancer cell populations (i.e. treatment-resistant cancer cells, metastatic/circulating cancer cells, cancer stem cells (CSC), and tumor-initiating cells (TIC)) (Corbet and Feron, 2017b). In our study, we already showed that such compounds able to interfere with glutamine metabolism but most importantly on the uptake and synthesis of lipids could block tumor growth in vivo. These findings allowed us to set up a high-throughput drug screening in order to identify new inhibitors targeting the metabolic pathways described above but also cytotoxic compounds that would take advantage of the avidity of acidosis-adapted tumor cells for exogenous fatty acids. It is noteworthy that some compounds of interest, able to interfere with fatty acid oxidation or synthesis, are currently under clinical development or already in use (perhexiline, trimetazidine, ranolazine) for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases; these molecules may therefore be rapidly translated in clinical trials with cancer patients.

Associated references

Corbet C. & Feron O. Tumour acidosis: from the passenger to the driver's seat. Nat Rev Cancer 2017a Oct;17(10):577-593. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2017.77

Corbet C. & Feron O. Emerging roles of lipid metabolism in cancer progression. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2017b Jul;20(4):254-260. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000381

Corbet C. & Feron O. Cancer cell metabolism and mitochondria: Nutrient plasticity for TCA cycle fueling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017 Aug;1868(1):7-15. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2017.01.002

Corbet C., Ragelle H., Pourcelle V., Vanvarenberg K., Marchand-Brynaert J., Préat V., Feron O. Delivery of siRNA targeting tumor metabolism using non-covalent PEGylated chitosan nanoparticles: Identification of an optimal combination of ligand structure, linker and grafting method. J Control Release. 2016a Feb;223:53-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.020

Corbet C., Pinto A., Martherus R., Santiago de Jesus J.P., Polet F., Feron O. Acidosis drives the reprogramming of fatty acid metabolism in cancer cells through changes in mitochondrial and histone acetylation. Cell Metab. 2016b Aug;24(2):311-23. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.003

Corbet C., Draoui N., Polet F., Pinto A., Drozak X., Riant O., Feron O. The SIRT1/HIF2alpha drives reductive glutamine metabolism under chronic acidosis and alters tumor response to therapy. Cancer Res. 2014 Oct;74(19):5507-19. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0705